Bio

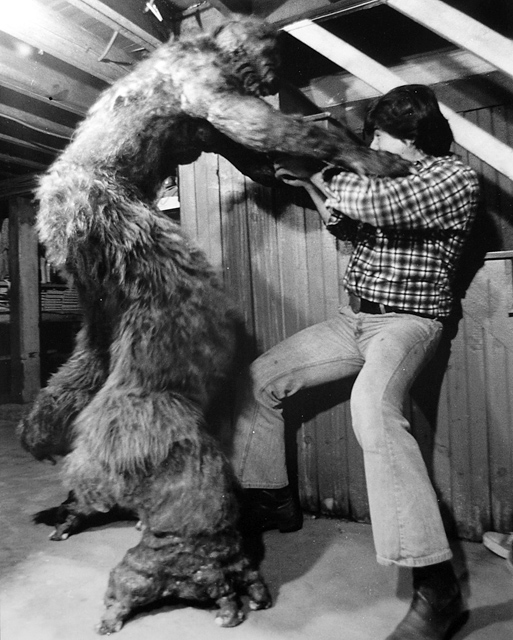

Don with director of photography Richard Geiwitz on the set of “Fiend” in 1980.

DON DOHLER: AN APPRECIATION

For the better part of 30 years, independent filmmaker Don Dohler, while failing to register on the mainstream movie-biz Richter scale, cranked out an entertaining skein of low-budget, no-stars horror and science-fiction motion pictures that earned him a worshipful cadre of international devotees: 90-minute features chockablock with decapitations, eviscerations, impalings, murderous nuclear families devoted to cannibalism or organ harvesting, thong-clad vampirettes, cleaver-wielding housewives, switchblade-flicking psychos, trigger-happy yahoos, marauding aliens, reanimated corpses, fog machines in overdrive, enough fake blood to fill several Olympic-sized swimming pools, and more running through woods than a battalion of Green Berets on maneuvers. From 1977’s The Alien Factor to 2006’s Dead Hunt, Dohler made a total of 11 films: all of them conceived–and several of them executed—at his home on a cul-de-sac in suburban Baltimore.

Hamstrung by what exploitation-movie connoisseur Joe Bob Briggs, in his review of Dohler’s 2001 Harvesters, termed “25-cent budgets”–actually, from a low of $4000 to a high of $42,000–and vexed by cold-footed investors, butter-fingered crew, and T&A-obsessed distributors, Dohler nonetheless persevered, infusing his films with a homespun charm, a deadpan wit, and a dogged DIY sensibility, even though at one point he grew so embittered with filmmaking that he forswore the business for a dozen years. Often, he accomplished the principal tasks solo–writing, directing, and producing his first six features, for the most part, on his own, before recruiting part-time actor Joe Ripple in 2000 to direct the movies so that he, Dohler, could concentrate on cinematography.

Dohler was, in effect, an auteur, if a reluctant one. If people never stopped and stared and pointed at him when he ambled along the aisles at the supermarket, they did clamor for his autograph at annual horror/science-fiction conventions. “Sci-fi and horror have a [built-in] market, especially low-budget [stuff],” the almost always courteous, congenial, and composed Dohler explained in a 2003 interview.

Although best known as a filmmaker, Dohler also worked for two decades, from 1986 to 2006, as a journalist, overseeing the operations of several community newspapers in the Baltimore area, and, additionally, served as the publisher/editor for a series of highly respected – and influential – small-press magazines delving into cinema appreciation and the nuts and bolts of moviemaking. The mechanics of filmmaking especially fascinated him, and he became particularly animated when discussing hardware and software, editing and sound design, location scouting and set construction.

“I’ve never really liked directing,” he confessed. “It was thrown on me by default when we made The Alien Factor. I prefer the behind-the-scenes kind of stuff–camera-work, editing.” Accordingly, do not parse for a thematic rune in Dohler’s work: “I’ve never gone into a film with any intent on inserting a subliminal message or philosophy. It’s strictly trying to make a story that’s entertaining.”

As a boy growing up in suburban Baltimore, Dohler feasted on 1950s horror and science fiction pictures each Saturday afternoon. Favorite films included 1956’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers, 1954’s Creature from the Black Lagoon, and anything made by stop-action special effects godfather Ray Harryhausen.

Dohler readily discerned–and relished–those films’ superiority to the connect-the-dots scarefests routinely dished out in the ’50s and early ’60s. “I saw very few of these really crappy B-movies that are now cult favorites,” he recalled. “Even then I didn’t like the bottom-of-the-barrel kind of movies.”

Conversely, he found 1956’s Forbidden Planet–essentially Shakespeare’s The Tempest in outer space–completely bewitching, speaking of it reverentially: “It was such an awe-inspiring movie to a kid, unlike anything we’d ever seen, because Hollywood’s big studios never made these types of movies–a big studio sci-fi movie with big production values and great effects.”

Forbidden Planet nudged young Don toward wanting to make his own movies. For a Christmas present in 1958, 12-year-old Dohler asked his mother for a movie camera, and received an 8mm Kodak. He and a childhood buddy immediately set about devising “crude and silly” kiddie productions, including one entitled The Mad Scientist.

Three years later he also became a teenage publisher, inaugurating Wild, a “version of Mad magazine,” as Dohler characterized it. The fanzine attracted contributions from like-minded enthusiasts, including cartoonists Skip Williamson and Art Spiegelman, who’d later achieve considerable notoriety–Williamson for his character Snappy Sammy Smoot, Spiegelman for his Maus graphic novel.

Wild lasted for 11 issues, petering out in 1963. This allowed Dohler, who’d ditched high school at age 16, to experiment further with his “crude and silly” homemade movies, eventually graduating to a Super 8 camera. By then he’d scored an office job with Eddie Leonard Restaurants in Washington, and in 1967 joined the D.C.-based Washington Society of Cinematographers (WSC), “a pretentious name for a bunch of amateur weekend moviemakers,” according to Dohler. “I started doing more serious efforts. They were still shorts, but they had plots and stories and characters and special effects.”

“Mr. Clay,” a 1967 movie of Dohler’s, featured a clay model that comes to life through stop-action animation.

In 1967’s stop-action Mr. Clay, for example, Dohler plays the protagonist, pitting himself against “this animated clay thing” that looks remarkably like the prototype for the perpetually victimized Mr. Bill on TV’s Saturday Night Live. Dohler upped the production values, building his own elaborate miniature sets, for 1968’s Pursued, creating the prototype for several of his later features with FBI-type agents and a mystery man on the run. “In the end,” he explained, “it turns out that he’s an alien, and he kills these two agents. Then you see this flying saucer take off from behind the trees.”

Emboldened by the profusion of underground comics popular at the time, Dohler merged his twin passions of publishing and sci-fi/horror amateur filmmaking in 1972 by launching Cinemagic, a magazine that he published out of his home. In addition to profiling aspiring moviemakers and their films, Cinemagic placed a critical emphasis on how-to articles, often written by the filmmakers themselves: “Creating a Giant Spider,” “Making a Miniature Flying Saucer,” “Creating Your Own Moon Surface.” Starting with a 1000-copy run, Cinemagic approached a 5000-copy circulation when, after 11 issues, Dohler sold it in 1979 to the publishers of genre heavyweights Starlog and Fangoria. “I was getting burned out by the whole mess,” he recalled, “and needed to get it off my back.”

The premiere issue of Cinemagic.

Meanwhile, catalyzed by a real-life incident considerably more frightening than anything depicted in the pages of Cinemagic, his filmmaking career got under way after years of dithering–“I had been talking with friends [about making a feature], but there was a lot of skepticism, like, ‘You don’t make movies in Baltimore.'” The date: January 27, 1976, Dohler’s 30th birthday. He was working in the D.C. offices of Eddie Leonard, where he’d ascended to the post of payroll manager. “Out of the corner of my eye I notice this guy walking through the offices,” he recounted. “I thought, ‘We’re getting robbed.'”

Sure enough, after barreling in, two gun-toting thugs laid siege to the premises, holding Dohler and two women co-workers hostage: “They had us on the floor, facedown, and I had a sawed-off shotgun held to the back of my head.” The company’s manager had departed only minutes earlier to make a bank deposit. “I said to these guys, ‘You’re gonna have to shoot me, because we can’t open the safe. We don’t know the combination.'” This Dog Day Afternoon scenario lasted for more than an hour, until the manager finally returned and opened the safe, whereupon the robbers vamoosed with bags of coins.

“Afterward, I called a friend of mine in D.C. who had dabbled in filmmaking,” Dohler continued, “and I told him, ‘I almost got killed today. I’m making a movie!'”

Bidding sayonara to his job, Dohler set about assembling the cast, crew, and investors for his debut feature: For cast he enlisted family, friends, some semi-pro actors, and a pair of local media celebs; for crew he tapped into the reservoir of amateur filmmakers he knew through Cinemagic and the WSC; and for investors he hit up eight different people, including his aunt, for $500 each. Filming on The Alien Factor began in October 1976.

“We were all kind of tripping over each other trying to figure out how to make a movie,” Dohler explained. “The whole thing was shot in a frigid, snow-covered environment.”

After overcoming a handful of rookie vexations in postproduction, Dohler, hoping to wow distributors and snag a theatrical deal, blew up his 16mm print to 35mm, scrounging $10,000 from already stretched investors for the purpose. When no serious offers materialized, the film’s fate looked bleak. Then serendipity intervened. With Star Wars registering in the box-office red zone in the summer of 1977, local TV stations craved product to sate the sci-fi zeitgeist. Through a friend of a friend, Dohler sold The Alien Factor to a television distributor as part of a 15-movie package. It showed on TV all over the U.S., as well as in some Spanish-speaking nations. And while The Alien Factor never snared a legitimate theatrical run, it popped up for local midnight screenings at Baltimore movie houses.

Actor Dave Geatty finds a surprise in his basement in this scene from “The Alien Factor.”

Over the next 10 years, despite a vexing series of setbacks concerning financing, distribution, and personnel, Dohler made four films – the gothic and claustrophobic Fiend; Nightbeast, a gore-fest about a deranged, truculent space invader; Galaxy Invader, wherein exploitative humans hector a benign alien; and the fanciful, family-that-slays-together fable Blood Massacre — for the then-burgeoning video market. (Dohler also cadged midnight showings of Nightbeast at a suburban theater over a weekend in April 1982. Posters screamed, “The Sci-Fi Thriller Made in Baltimore!”)

But ultimately, in the late 1980s, after experiencing exasperation after exasperation associated with low-budget filmmaking, Dohler quietly quit the business: “I just said, ‘This is just too aggravating. The hell with this.'”

While loath to resume moviemaking, he nonetheless remained an ardent aficionado of classic 1950s horror/sci-fi, and, in 1993, co-founded the literate film appreciation magazine Movie Club. Unlike the how-to articles featured in Cinemagic, Movie Club celebrated the genre’s heyday with a dozen themed issues–killer plant movies, haunted house movies, female monster movies–before giving up the ghost in 1997.

Two years later, Dohler succumbed to the allure of making movies again. “I guess I just never shook it,” he confessed. His tabula rasa was Alien Rampage, shot for $35,000 in late 1999/early 2000. Joe Ripple, a local police officer at the time, played an FBI agent and performed several production chores on Alien Rampage. Eager to divest himself of directing duties and assume full-time cinematography responsibilities, Dohler invited Ripple to handle the next film; Ripple agreed.

The division of labor established, they formed a partnership, Timewarp Films, in the summer of 2000, selecting as their initial venture Harvesters, in essence a shave-and-a-haircut of Blood Massacre, shooting in digital video instead of film.

Satisfied with their collaboration, the duo knocked out a pair of fanged features — Stakes and Vampire Sisters — followed by the Agatha Christie-esque Dead Hunt. Not long after the latter’s premier in June 2006, Dohler learned that he had contracted cancer, stoically and uncomplainingly undergoing a series of debilitating treatments in an effort to stem the disease. They proved unsuccessful, and he succumbed to cancer in December 2006, age 60. (Timewarp’s Crawler was in post-production at the time of his death.)

Don Dohler never entertained unrealistic notions about his status in the cinematic universe, toiling for many years in relative obscurity while insisting that simply making movies sustained him. In a moment that both encapsulated his personal temperament and defined his filmmaking philosophy, he evinced a lack of concern about the prospects of Vampire Sisters when wrapping that film. “I don’t expect gangbusters from it,” he shrugged, “but it just might be quirky enough that it takes off. Who the hell knows?”

—Michael Yockel